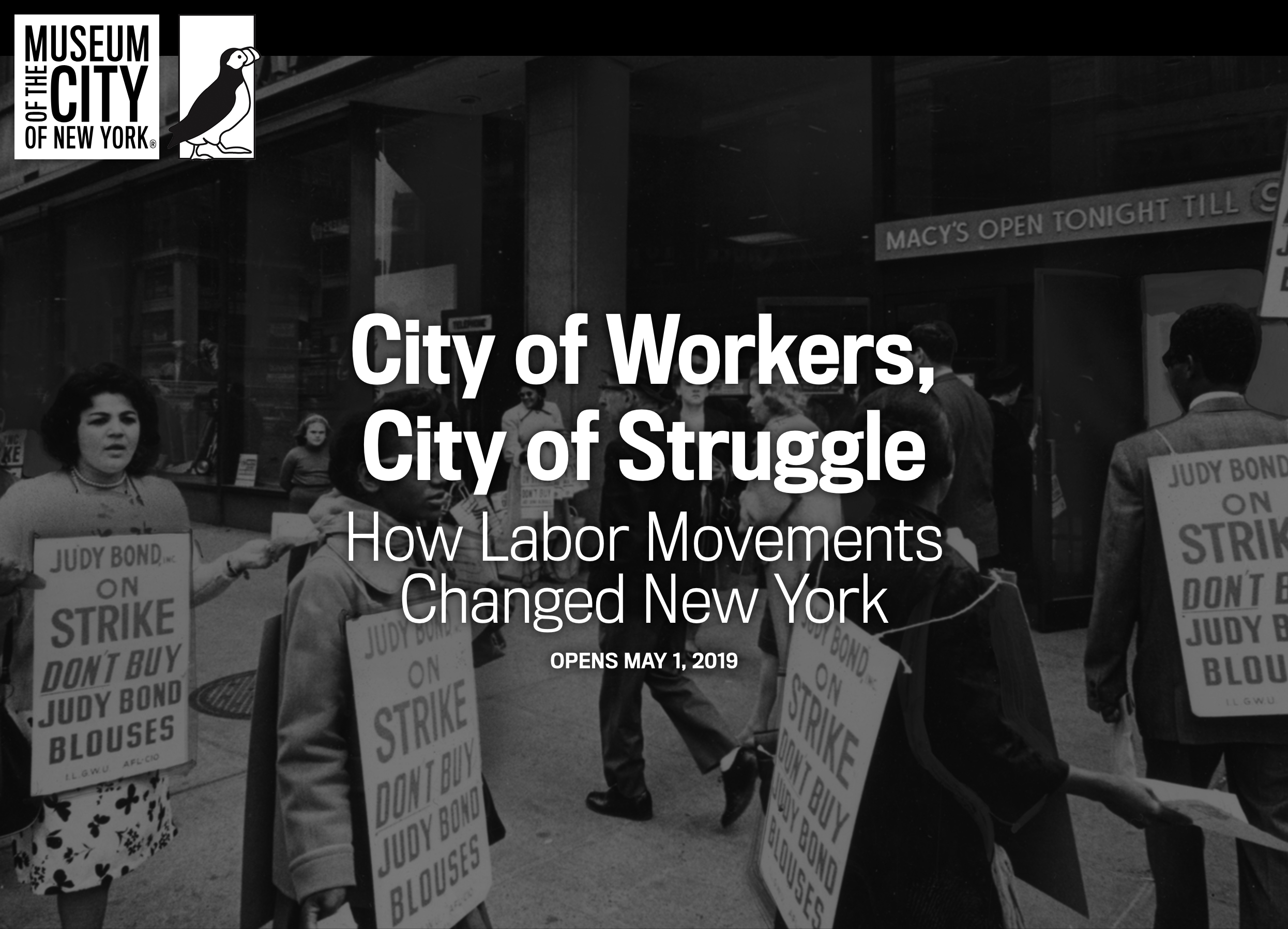

City of Workers, City of Struggle

The exhibit is a fascinating look at the vital and important history of labor movements in the City of New York. It opens on May 1st at the Museum of the City of New York.

PRESS RELEASE:

City of Workers, City of Struggle

Opens at the Museum of the City of New York on May 1

New Exhibition Examines How Labor Movements Transformed New York

(New York, NY, April 29, 2019) City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York, opening at the Museum of the City of New York on May 1, will trace how New York became the most unionized large city in the United States. For more than two centuries, New York City has been an incubator and battleground of movements by and for working people and today, 24 percent of New York City workers are unionized, compared to the national average of 11 percent. This exhibition will examine the social, political, and economic story of the diverse workers and movements in New York through rare documents, artifacts, photographs, archival film footage, and interactive features.

“You cannot understand the history of New York City without understanding the history of labor movements here,” said Whitney Donhauser, Ronay Menschel Director and President of the Museum of the City of New York. “Through this exhibition, visitors will learn how labor movements evolved over two centuries in New York, the current state of affairs for workers, and what the future may hold.”

“Labor movements have been central to the rise of the city that we know today. It’s exciting that City of Workers, City of Struggle explores New York’s rich labor history, and also gives voice to contemporary labor activists and working people as they face the opportunities and challenges of a rapidly changing urban economy,” said Steven H. Jaffe, curator of the exhibition.

City of Workers, City of Struggle will follow the progression of the labor movement by breaking the history into four segments and then looking toward the future. The exhibition begins with the section “In Union There is Strength,” which documents the 19th century when there was a shift from the artisan to wage worker through the development of new patterns of work and employment, as well as new technology. This will be exemplified in the exhibition by an enormous wrench used to build the Brooklyn Bridge. It will also include an illustration of the day in 1882 when New York’s Central Labor Union launched the nation’s first Labor Day to underscore Labor’s efforts to secure better pay, hours, and working conditions.

The exhibition moves on to the period of 1900–1965 with the section “Labor Will Rule,” looking at an era when New York’s unions gained monumental power. By 1950, New York City had about one million union members representing at least a quarter of the entire workforce. However, this power was not equally shared as female, African American, Latino, and Asian American New Yorkers still fought obstacles to their presence in union ranks and leadership.

“Sea Change,” the third section, focuses on the years between 1965 and 2001. Over the preceding decades, hundreds of thousands of new immigrants had joined African Americans from the South and Puerto Ricans in coming to New York to seek opportunity. The city’s fiscal crisis in 1975, and a growing anti‐union mood in local and national politics, led to challenges for the movement to organize labor. These developments coincided with court and federal agency decisions that scaled back legal protections earlier won by organized labor. Together, they began a long weakening of unions’ economic and political power, as many New Yorkers worried about the costs of union contracts to the city and as the number of unionized workers declined nationwide. Between 1960 and 2000, New York City lost more than 650,000 manufacturing and port jobs as businesses automated or moved away in pursuit of lower wages and taxes, and fewer regulations.

By the 1970s, a new militancy fueled the activism of previously marginalized workers: women, African Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Asian Americans were challenging union establishments. As union membership declined in private industry, organizations of government employees and service workers (hospital, maintenance, security, clerical, and others) increasingly became engines of upward mobility for thousands of New Yorkers.

The last section, “New Challenges,” looks at how New York activists after 2001 continued to reshape the future of labor by broadening the agenda to confront issues ranging from racial profiling to sexual violence, LGBTQ equality, environmental safety, and citizenship status. Worker Centers and other new community organizations used foundation grants, legal action, and public pressure to help non‐unionized and undocumented workers. In a changing economy, this “Alt Labor” or “New Labor” movement also mobilized people who worked as freelancers or in a succession of jobs.

Although New York remains the most unionized city in the United States today, current realities are challenging. Conflicting visions for the city’s future have sometimes pitted different groups of organized workers against each other. Yet local labor activists have also achieved important recent victories, including paid family leave, guaranteed sick leave, and a $15 minimum wage. The exhibition is organized by curator Steven H. Jaffe with the help of a distinguished panel of scholars.

A companion publication takes a deeper dive into some of the topics touched in the exhibition. City Workers, City of Struggle features essays by leading historians of New York along with vivid depictions of work, daily life, and political struggle. Edited by Joshua B. Freeman, Distinguished Professor of History at Queens College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, it is published by Columbia University Press and is available for $40 in the Museum shop.

City of Workers, City of Struggle is presented in collaboration with the Kheel Center at the School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University and the Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at NYU.

City of Workers, City of Struggle, its associated programs, and its companion publication are made possible through the generous support of The Puffin Foundation, Ltd.

Additional support for the exhibition’s companion publication is provided by Atran Foundation, Inc., and Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund, and other generous donors.

Exhibition Committee

Governor David A. Paterson, Co‐Chair

Patricia Smith, Co‐Chair, Senior Counsel, National Employment Law Project Law Project; former New York State Commissioner of Labor

Vincent Alvarez, President, New York City Central Labor Council, AFL‐CIO

Esta R. Bigler, Director, Labor and Employment Law Program, Cornell University ILR School Marco Carrión, Commissioner, Mayor’s Office of Community Affairs

Janella T. Hinds, UFT Vice President, Academic High schools, United Federation of Teachers Ed Ott, Active in the Labor Movement for more than 50 years

Roberta Reardon, Commissioner, New York State Department of Labor

Lorelei Salas, Commissioner, New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection

Maritza Silva‐Farrell, Executive Director, ALIGN: The Alliance for a Greater New York

Lara Skinner, Executive Director, The Worker Institute, Cornell University ILR School

Kathryn Wylde, President and CEO, Partnership for New York City

Scholarly Advisory Committee

Joshua B. Freeman, chair, Rachel Bernstein, Michelle Chen, Margaret Chin, Richard Greenwald, Louis Hyman, Alice Kessler‐Harris, Richard Lieberman, Stephen McFarland, Premilla Nadasen, Kimberly Phillips‐Fein, Christopher Rhomberg, Aldo Lauria Santiago, Robert W. Snyder, Michael Spear and Clarence Taylor.